The Life and Times of Harry Bridges (1901 - 1990)

An article by Grif Fariello"I was just a working stiff who happened to be around at the right time"

Throughout his life Harry Bridges was many things: a seaman, a longshoreman, a union organizer, a world-renowned labor leader; and in his later years, a San Francisco Port Commissioner and President of the California Congress of Seniors. Throughout it all, Harry never lost his passion for democracy and his commitment for a better world for all people. It is unmistakable how large his accomplishments were, how singular his character and integrity. There is also no mistaking how strongly the spirit of Harry Bridges animates the heart and soul of San Francisco, the city he adopted as his home, and the city he loved. For it was Harry and the working men and women of 1934 who laid the foundations that built San Francisco into the progressive city it is today. Twenty tons an hour

A native Australian, Bridges left his Melbourne home at the age of

fifteen for a life at sea. In 1920, he came ashore for good in San

Francisco. At that time, San Francisco was known as the most productive

port in the world. The waterfront held 17 miles of berthing space; 82

docks capable of berthing 250 vessels at one time. It was a port of call

for more than 118 steamship lines, with more than 7,000 ships arriving

and departing yearly. In 1929, freight tonnage in and out of the Golden

Gate amounted to more than 31 million tons. San Francisco shipping and

stevedoring companies took pride that San Francisco had one of the most

cost-efficient longshore workforces in the country. A gang of sixteen

men could move -- by hand -- upwards of twenty tons an hour, and a crew

of a hundred men could load a three-thousand ton steamer in just two

days and a night, stowing enough cargo to fill a train of freight cars

five miles long. The American-Hawaiian Steamship Company calculated that

during the years 1927-1931 their agents paid, on average, $0.99-1.03 per

ton for loading in San Francisco, compared to $1.85-1.99 in New York and

$2.17-2.43 in Boston. But the port of San Francisco was also known for

the worst working conditions in the world -- and the deadliest.

A native Australian, Bridges left his Melbourne home at the age of

fifteen for a life at sea. In 1920, he came ashore for good in San

Francisco. At that time, San Francisco was known as the most productive

port in the world. The waterfront held 17 miles of berthing space; 82

docks capable of berthing 250 vessels at one time. It was a port of call

for more than 118 steamship lines, with more than 7,000 ships arriving

and departing yearly. In 1929, freight tonnage in and out of the Golden

Gate amounted to more than 31 million tons. San Francisco shipping and

stevedoring companies took pride that San Francisco had one of the most

cost-efficient longshore workforces in the country. A gang of sixteen

men could move -- by hand -- upwards of twenty tons an hour, and a crew

of a hundred men could load a three-thousand ton steamer in just two

days and a night, stowing enough cargo to fill a train of freight cars

five miles long. The American-Hawaiian Steamship Company calculated that

during the years 1927-1931 their agents paid, on average, $0.99-1.03 per

ton for loading in San Francisco, compared to $1.85-1.99 in New York and

$2.17-2.43 in Boston. But the port of San Francisco was also known for

the worst working conditions in the world -- and the deadliest.

By 1919, the waterfront and maritime unions which had first organized in 1853 and made San Francisco the premiere union port in the world had been violently suppressed. Legal protections for maritime workers were non-existent. For centuries law and custom had regarded maritime workers as less than human, more chattel slaves or pack animals. As late as 1897, the Supreme Court had denied seamen the protections of the 13th Amendment banning slavery and involuntary servitude. The court ruled that they were "deficient in that full and intelligent responsibility for their acts which is accredited to ordinary adults."

With the employers now firmly in control, working conditions declined to their lowest point in history. Longshoremen were selected like cattle in the humiliating ritual of the "shape-up" where thousands of desperate men circled up for hours in all weather to beg for a job. The lucky few were required to kick back a portion of their pay for the opportunity. It might take a man three or four days to connect with a job, sometimes as long as a week. Once on the job, they worked under the speed-up, a killing pace enforced by the Walking Bosses, the company foremen who held the threat of the blacklist for any man who fell behind. Crews were often forced to race one against the other to see which might load the faster. A man might hunt for days for a job that lasted only a few hours, but work shifts often ran as long as 24 or 36 hours without rest. Even longer shifts of 58 and 72 hours were not uncommon. The longest longshore work shift ever recorded ran for 110 hours straight. Two men died on the job; five others were never able to work again.

Those who dropped from exhaustion or heart attack or who were injured or killed on the job could be easily replaced from the pool of hungry men at the pierhead. It was not unusual for a man to obtain work through the misfortune of a fellow worker. Throughout the 1920s, working longshoremen were disabled at the rate of three to six for every eight hours on the job. Yearly, the number of accidents reported equaled the number of workers. And since reporting a accident meant running the risk of the blacklist, many accidents were never reported at all. The death rate for longshoremen through industrial accidents and job induced disease was the highest for any occupation in the country - 62% above normal. On average, a longshoreman could expect to die before his 47th birthday. The pay averaged $10.45 per week.

The I.L.W.U.

Out of these deplorable conditions grew one of the most democratic and progressive labor union in the United States and also one of America's greatest labor leaders, Harry Renton Bridges. Within 15 years of his arrival he would be at the head of an insurgent labor movement that would become the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), a union that would transform the lives of workers from San Pedro to Ketchikan and into Canada, over to Hawaii, and inland to Chicago and Baltimore, as far south as New Orleans.

Harry's inspired leadership through the eighty-three days of the 1934 coastal strike and the three days of the San Francisco General Strike brought the waterfront employers to the bargaining table, ultimately winning agreements that finally allowed dock workers and seamen to work with dignity. Agreements that would last, in one form or the other, into the 21st century.

"Labor in San Francisco is licked."

By the beginning of 1934 Harry Bridges found himself at the head of the

Albion Hall group of labor activists. Named for the rented hall in which

they met, these men had put in years of organizing, working to establish

the International Longshoremen's Association (I.L.A.) as a single unit

along the entire West Coast. Many of the establishment leaders of the

other city unions were wary of Harry and his group, but their own rank

and file backed the straight-talking Australian. This was no more

evident than with the Teamsters, who were crucial to the success of the

longshoremen as it was they who hauled the freight to and from the

docks. The waterfront was rife with tension. Talk of a general strike

was in the air.

By the beginning of 1934 Harry Bridges found himself at the head of the

Albion Hall group of labor activists. Named for the rented hall in which

they met, these men had put in years of organizing, working to establish

the International Longshoremen's Association (I.L.A.) as a single unit

along the entire West Coast. Many of the establishment leaders of the

other city unions were wary of Harry and his group, but their own rank

and file backed the straight-talking Australian. This was no more

evident than with the Teamsters, who were crucial to the success of the

longshoremen as it was they who hauled the freight to and from the

docks. The waterfront was rife with tension. Talk of a general strike

was in the air.

On May 9, 1934, after a month of fruitless negotiations, the longshoremen struck for recognition. The Teamsters joined in and every port on the west coast shut down. Not long after, the beleaguered seagoing unions joined the strike. The seamen also worked under terrible conditions. With the coming of the Great Depression, the shipping companies had seized the opportunity to squeeze out even more profits. Even though the construction of their fleets had been ninety percent subsidized by taxpayers, and even though they received additional millions of dollars yearly through the carrying of U.S. mail overseas, the shipowners took advantage of the sudden pool of unemployed. To the critics of these subsidies they had claimed the necessity of paying "good American wages," yet they now drove these wages down so steeply that desperate seamen were forced to pay $5 and up for jobs that paid one-cent-a-month plus room and board. The jobs were called "workaways." They worked 16 and 18 hour shifts, and the food was so bad it reportedly would sicken a goat.

This was the first industry-wide strike in history. It was unionism built by the members and a strike run by the members. Contributions flooded in from every direction Ð from unions, organizations, and private individuals up and down the coast. Farmers sent truckloads of produce to the striker's relief kitchens.

The ship owners and their allies were also prepared. They believed this was the opportunity to deliver the final blow to organized labor on the docks. Banker William H. Crocker called it "the best thing that ever happened to San Francisco. It's costing us money, certainly. But it's a good investment, a marvelous investment. It's solving the labor problem for years to come, perhaps forever. When the men have been driven back to their jobs, we won't have to worry about them anymore. They'll have learned their lesson. Labor in San Francisco is licked."

The waterfront employers attempted to recruit replacement workers from

the African-American community, a group long marginalized on the

waterfront. This was the traditional method to break a strike, pit

worker against worker along racial lines. But they soon discovered that

Harry had been there before them. He had gone to the churches and the

meeting halls. He had acknowledged the injustices that had plagued that

community for so long and promised that in this new union he was

fighting to create there would be no color line. The union would open

full membership to African-Americans based not on the hue of their skin

but solely on the strength of their hearts for the struggle ahead. "All

workers must stand together," he told them. "There can be no

discrimination because of race, color, creed, national origin, religious

or political belief. Discrimination is the weapon of the boss."

The waterfront employers attempted to recruit replacement workers from

the African-American community, a group long marginalized on the

waterfront. This was the traditional method to break a strike, pit

worker against worker along racial lines. But they soon discovered that

Harry had been there before them. He had gone to the churches and the

meeting halls. He had acknowledged the injustices that had plagued that

community for so long and promised that in this new union he was

fighting to create there would be no color line. The union would open

full membership to African-Americans based not on the hue of their skin

but solely on the strength of their hearts for the struggle ahead. "All

workers must stand together," he told them. "There can be no

discrimination because of race, color, creed, national origin, religious

or political belief. Discrimination is the weapon of the boss."

There was no lack of heart. During the hard months ahead, the African-American community stood by the longshoremen and the longshoremen stood by their promise. A promise that is enshrined in the constitution of the I.L.W.U. and is fiercely defended to this day.

Arrayed against the strikers were the shipowners, the Associated Farmers of California, the Employers Industrial Associations up and down the coast, the American Legion, and several vigilante groups, which in connivance with the police and employers loosed a unrestrained reign of terror. Unionists were assaulted on the streets and in their homes, meeting halls were destroyed, organizations friendly to the strikers were raided and their members beaten. After one such raid on a small pro-union group, the hallways and staircases were found slippery with blood.

After more than two months of stalemate and several police attacks upon the strikers (including one in which 250 high school students were clubbed bloody on National Youth Day), the employers decided to open the docks. The key port of San Francisco was their target. If they could crush the revolt in San Francisco, then the coastwide strike would collapse.

What followed on the two days of July Third and Fifth was brutal street fighting between thousands of strikers and police Ð an uneven struggle, angry and bloody, pitting the fists and boots of unarmed union men against clubs and riot guns, nausea gas and revolvers. But it is the final day -- a desperate twelve hour battle that raged up and down the Embarcadero Ð that is now remembered as "Bloody Thursday."

That day began with the 5,000 striking workers lining the inland side of the Embarcadero, facing off the thousands of armed policemen and vigilantes who guarded the docks. Pier 38 was to be opened. Hot cargo waited on the trucks idling behind the metal gates of the pierhead. If that cargo could be moved to the warehouse just blocks away, then the employers could claim a victory. The longshoremen knew full well what that meant - their children would remain hungry, their wives old before their time, their own lives cut short and brutalized. They were determined never to see that day.

At eight AM, a prowl car pulled to a halt between the lines. A Police Captain rode the running boards. He called out, "Let'em have it, men!" The police emptied their riot and gas guns into the line of strikers. The unionists recoiled, but held their ranks. The next moment they surged forward and the battle was joined.

Witnesses of that day claim the men fought and fell in silence. The only sounds to be heard were the crack of clubs against skulls, the report of gunfire and exploding gas canisters, the wail of sirens. Scattered groups of men slugged it out against the swinging clubs, while others retreated under the onslaught only to regroup and join the fray again. Several hundred unionists were driven back up the slopes of Rincon Hill, then under preparation for construction of an anchorage for the Bay Bridge. There, the men threw up barricades from the debris of demolished buildings to protect themselves from gunfire. From their positions they hurled brickbats down the slope at the police.

Three assaults were mounted against the men on Rincon Hill. The first was a wave of policemen on foot, the second a charge on horseback. Both were driven back by the strikers. The third was also on horseback, but prepared for with a sustained volley of gunfire and a curtain of gas laid across the crest of the hill. The exploding canisters ignited the dry grasses and the slopes were soon a raging inferno. The horsemen pounded through smoke and gas to gain the heights. But when they leapt the barricade, there was not a striker in sight. They had simply slipped away. Police took command of the hill and surrounded it with guards to prevent recapture.

All morning long the battle raged. Already the possibility of maintaining a picket line on the Embarcadero in the face of gunfire and gas appeared hopeless. Then, at 12 noon, in almost a surreal moment, both sides broke for lunch. It was as if a whistle had blown and all had retired to observe a time-honored ritual. Policemen headed for their lunch buckets and strikers from all positions drifted back to their headquarters at the corner of Steuart and Mission where they had established a mess hall. Most of the fighting had occurred within an out-of-way industrial district along the south end of the Embarcadero, but the striker's headquarters was in the heart of downtown, a block off Market Street and a stone's throw from the busy terminus of the Ferry Building. Thus situated, it had long been considered by the longshoremen as a neutral zone. So, when, shortly after 1 o'clock, the police staged their most crushing attack, the strikers were taken entirely by surprise.

A police car pulled to halt in the middle of the intersection. Tear gas shells were fired through the windows of the Longshore Hall and thick smoke filled the rooms, already filled with the injured. The men emptied the building and scattered in confusion, only to encounter lines of policemen driving them toward the downtown area. Then the shooting began. Riot guns and pistols. Men fell. Streetcars were abandoned as stray bullets crashed through the windows. One woman fled a stalled trolley only to be dropped by a glancing shot to the temple. A man in a business suit ran to her aid. He too fell. Ironworkers clinging to the towers of the Bay Bridge scrambled down their ropes for safety as sporadic rounds droned around them. The battle swept onto Market Street. A Chronicle reporter described the scene:

Women who had been shopping in downtown stores stepped into an inferno. With screaming children clinging to them, they found themselves in clouds of tear gas. Guns cracked. Men fell screaming as they went down. Police clubs cracked against skulls.

Smothered and blinded by the gas, the women and children staggered about helplessly. Police grabbed them fast as possible and sent them to the hospital where they were horrified by the sight of men dripping with blood, moaning from bullet wounds and injuries.

The fight raged until mid-evening. Thirty-three men and women had been shot, strikers and by-standers alike. Two men lay dead: Howard Sperry, a longshoreman and veteran of the First World War; and Nick Bordoise, a cook who had volunteered at the mess hall. Both had suffered multiple gunshot wounds to the back. The total number of injured is unknown, but was estimated in the hundreds.

In the midst of the bloodshed, Harry Bridges had led a contingent of strikers to the office of Mayor Rossi. "You've got to call off the police," pleaded Harry. "People are dying out there."

"You started this, Bridges," replied Rossi. "Now take the consequences."

That evening, Governor Merriam ordered the National Guard onto the waterfront. Two thousand troops marched into the area armed with Browning Automatic Rifles, .30 caliber machine guns, and bayoneted Springfields. Along with them came a squad of small tanks, known as whippets. They occupied the entire waterfront and mounted their machine guns atop the piers and along the Embarcadero in sandbagged nests. By now, the employer's trucks were running freely from Pier 38 to the warehouses.

Police Chief Quinn remarked, "I don't know why the National Guard is necessary. The police have the situation well in hand."

Harry Bridges told his men. "We can't fight the police and machine guns and the National Guard."

Late that night, a reporter boarded a trolley car on his way home from work. He asked the conductor if he believed there was going to be a general strike. The man replied, "You can bet your damned life there will." The City Reacts

Up to this point, the San Francisco newspapers had been firmly in the camp of the employers. But now their very headlines seemed to recoil in horror at the choice: "S. F. Waterfront Rocked By Death, Bloodshed, Riots."

"BLOOD FLOODS GUTTERS AS POLICE BATTLE STRIKERS!"

Newsboys cried "Murder! Murder on the waterfront!" at the top of their lungs. Newsmen who had been in the thick of the fight all day had been beaten with the rest. So much they had seen that day. Blood was the word that ran through their copy. Blood, with all it's variants of motion and color.

Blood ran red in the streets yesterday.

San Francisco's broad Embarcadero ran red with blood yesterday.

The color stained clothing, sheets, flesh.

Dripping. Human blood, bright as red begonias in the sun.

A run of crimson crawled toward the curb.

Most of us came to hate the sight of red.

There was so much of it.

Bloody Thursday. The events of that day vibrated through the city. Homes, meeting places, and bars ran loud with talk. Eyewitnesses recounted over and again the events they had seen. Door bells and telephones rang. Questions were asked, opinions voiced. Citizens of San Francisco had been shot down in cold blood. The city was boiling with anger. A general strike was fermenting.

The old-time conservative labor officials were determined to block a general strike at all costs. Yet the demands from their membership was so overwhelming they dared not oppose it too frankly. They quickly formed themselves into the "Strike Strategy Committee," whose duty it would be to work out a common program for all San Francisco labor. The maritime unions were carefully excluded from representation. "We are not considering a general strike at all," the chairman of the committee reassured reporters. "There is no danger of a general strike at all."

At that very moment, the rank and file of fourteen unions were voting overwhelmingly in favor of a general strike. That evening, two thousand teamsters crowded shoulder to shoulder into Dreamland Auditorium. Mike Casey, their conservative leader, warned that a strike was contrary to union rules and that they would lose benefit funds from the international if they took such an action. Their AFL charter might be forfeited, the union could be ruined. His protests were drowned in laughter.

Voices cried out, "Bridges! We want Bridges!" Catcalls and whistles split the air. "We want Bridges!" Casey's voice was swamped by the noise.

Several teamsters ran out to where Harry waited with the maritime workers. The salaried officials had had not even bothered to invite him to the meeting. He entered the hall to a deafening ovation. He spoke to the men in his quiet way, reminding them of the lessons learned from the strikes of '01, '16, and 1919. "The entire labor movement faces collapse if we maritime workers are defeated," he told them. "If you fellows join us, you will double our power." Casey called for the yes votes, and all two thousand hands went up. The teamsters would join the general strike, no matter what the Strategy Committee decided.

But the success of a general strike would depend on more than the solidarity of organized labor. Without the support of the ordinary citizens, any such action would face tough sledding indeed. Public opinion was crystallizing rapidly at opposite poles. San Francisco was a city divided, and in between lay a mass of neutrals Ð those who didn't know what was going on or could not understand it.

The following Sunday, Harry Bridges led a delegation of longshoremen to the offices of Police Chief Quinn. They requested permission for a funeral parade on the following day in order to bury their dead. "You keep the cops away," said Harry, "and we'll maintain order and direct traffic."

Quinn was aware of the public resentment that had been aroused and wished to placate it. "Okay," he relented. "But no union banners, no speeches. We'll stay away as long as you keep order. But if you don't . . ."

Monday was July 9th. In the early morning, crowds began to gather in front of the Longshore headquarters at Steuart and Mission. By noon, a living sea of people crowded Steuart Street from one end to the other. More than 40,000 men, women, and children from every trade and profession stood silently with hats off in the hot sun, waiting for the procession to begin.

The two coffins were loaded onto trucks. A union band struck the slow cadence of Beethoven's funeral march. Slowly, the trucks moved onto Market Street. The procession followed, headed for Dugan's Funeral Parlor near the corner of 17th and Valencia. The mourners marched ten abreast. A great mass, moving silently, their heads bared. The sidewalks were crowded with citizens. Hours passed, but still the mourners poured onto Market Street, until the entire length of the way, from the Ferry Building to Valencia, was filled with silent marching men, women, and children. Streetcarmen stopped their cars along the march, removed their caps. On the sidewalks, business men in suits doffed their hats. Parents pressed their children to the fore, instructing them in whispers, "Remember this. Don't ever forget."

Newspapers described it:

A river of humanity flowed up Market like cooling lava . . . the solemn strains of dirges and hymns . . . unaccountable thousands of spectators lining the streets with uncovered heads . . . overhead a brilliant sun in a cloudless sky.

The reporters commented on the men in the coffins:

In life they wouldn't have commanded a second glance on the streets of San Francisco, but in death they were borne the length of Market Street in a stupendous and reverential procession that astounded the city.

Even the hostile Industrial Association bowed to the power and dignity of the march. In their official record of the strike they wrote:

It was one of the strangest and most dramatic spectacles that has ever moved along Market Street. Its passage marked the high tide of united labor action in San Francisco.

As the last marcher broke ranks, the certainty of a general strike, which to many had appeared as a visionary dream of a small group of radicals, became for the first time a practical reality.

"We've got to have bloodshed . . ."

On July 12th the General Strike began. At 7 am all transportation of freight and merchandize halted as the Teamsters joined the 25,000 maritime workers now on strike. Two hundred butchers walked out of the slaughter houses; 1,500 more followed from the retail stores. Light rail and cable car drivers braked their cars to a halt. Cabbies returned their taxis to the barn and walked home. Boilermakers walked out of sixty shops. Bartenders, cooks, and waiters, shop girls and secretaries, shoeshine boys and newsies all joined. Two thousand six hundred laundry drivers and workers walked out.

Pressed by reporters on what actions the Strike Strategy Committee would now take, their spokesman refused to elaborate but he did say, "Do you fellows have to see a hay-stack in the air before you know which way the straw is blowing?"

Placards were plastered in the windows of mom and pop stores all across town: "No business until the boys win!" "Closed for the duration." The citizens of San Francisco had joined with organized labor. With one voice they said, "No business as usual until this wrong has been made right." In Oakland, upwards of 47,000 workers joined the 50,000 on strike in San Francisco. All in all, more than 125,000 citizens, from all walks of life, union and non-union alike, participated in the General Strike.

Later that day, a reporter stopped his car in the middle of a deserted Market Street and listened to the silence. "It was as if the entire city was asleep," he wrote. Then he heard a steady tapping he couldn't identify. At the far north end of Market, he spotted a lone woman walking in the middle of the street, the sound of her high heels echoing against the buildings.

Governor Merriam sent an urgent telegram to President Roosevelt, then observing Naval maneuvers off the coast of California. "Bolshevik army has invaded San Francisco," read the wire. "Federal troops needed. Urgent." Reportedly, FDR replied to his secretary, "Wire the good governor not to excite himself. There is no invading army. You tell him that's just Harry Bridges."

The reaction from the Waterfront Employers Association was inevitable and predictable. Shipowner Roger Lapham was their spokesman in a phone call to Madame Perkins, the Secretary of Labor. "We can cure this thing best by bloodshed." Lapham told her. "We've got to have bloodshed to stop it. It is the best thing to do."

"Isn't that a pretty dangerous outlook?" replied the Secretary, "and a pretty dangerous thing to rely on?"

"I think it's the best thing that could happen," said Lapham, "and the best way out for us all."

The employers believed all their troubles would be solved if they only

could be rid of one troublemaker - Harry Bridges. Harry was now at the

head of the Strike Committee, a committee hard at work ensuring adequate

supplies of food, medicine, and all other necessary essentials for the

city. He was also busy testifying before the National Longshoremen's

Board, an attempt by the federal government to gather the facts

necessary to a peaceful settlement. There he spoke at length,

extemporaneously and without notes. His presentation was so powerful

that even the employers would later remember it as "extraordinary,"

recalling his astonishing command of the facts and his command of

language. One of them would later write, "Employers were able for the

first time to understand something of the hold which he had been able to

establish over the strikers both in his own union and in the other

maritime crafts."

The employers believed all their troubles would be solved if they only

could be rid of one troublemaker - Harry Bridges. Harry was now at the

head of the Strike Committee, a committee hard at work ensuring adequate

supplies of food, medicine, and all other necessary essentials for the

city. He was also busy testifying before the National Longshoremen's

Board, an attempt by the federal government to gather the facts

necessary to a peaceful settlement. There he spoke at length,

extemporaneously and without notes. His presentation was so powerful

that even the employers would later remember it as "extraordinary,"

recalling his astonishing command of the facts and his command of

language. One of them would later write, "Employers were able for the

first time to understand something of the hold which he had been able to

establish over the strikers both in his own union and in the other

maritime crafts."

It was also around this time that the first attempt against Harry's life occurred. Harry had arrived home late one night, his nine-year-old daughter Kathleen in the car. He pulled into the darkened garage and exited the car. As he did, a man came from the shadows, a shotgun to his shoulder. He pointed the weapon at Harry. But as he did, Kathleen ran from the car and grabbed onto her father's leg. Harry pushed her away, attempting to move his daughter from the line of fire. She wouldn't budge. The stranger with the shotgun hesitated. From the side door came a voice. "Kill 'im! Kill 'im now!" The man raised his weapon again, but then he shook his head.

"I didn't get paid to kill no little kid," he said, and ran from the garage.

The identities of the would-be assassins were never discovered, nor was it ever known who exactly had hired them. But it is known that earlier the captains of industry arrayed against Harry had frankly and openly discussed his murder. Paul Smith, who would later become the Editor-in-chief of the Chronicle, had attended that particular meeting as a representative of his newspaper. He was a young man then, just twenty-six. Astounded at the plan they so calmly discussed and barely able to credit his ears, he rose in anger and denounced them all. He told them that if they didn't renounce any such plans immediately, he would ensure that every newspaper in the country knew of it, and further, that he would quit his job and volunteer to be Harry's bodyguard. The others in the room quickly assured the young man that he had misunderstood them, that they would never even contemplate such an act.

Three days after the start of the General Strike, both sides agreed to arbitration by the National Longshore Board. The industrial interests had been pressured by their bankers, who frankly suggested "give them the closed shop." The board awarded the longshoremen all of their demands, including a jointly managed hiring hall, with the all-important position of dispatcher to be appointed by the union. This ensured that the work would be distributed amongst the men fairly and without prejudice, and that the hiring hall could not be used to dispatch non-union men to the job during a strike. Not long after, the seamen won their demands as well. Now, maritime workers at sea and on shore would no longer work under the worst conditions in industrialized America. Now, they and their families would have a future.

Social and economic justice for all

Outspoken and blunt, Harry Bridges remained dedicated to the welfare of

working men and women for the rest of his life. It was qualities such as

these that galvanized workers across the country. He played a key role

in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a

powerful, progressive force in American labor and American life, and

soon headed the Pacific District.

Outspoken and blunt, Harry Bridges remained dedicated to the welfare of

working men and women for the rest of his life. It was qualities such as

these that galvanized workers across the country. He played a key role

in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a

powerful, progressive force in American labor and American life, and

soon headed the Pacific District.

For more than sixty years, Harry Bridges and his union have stood as a beacon for racial justice, equality across race, creed, and gender, mutual understanding and world peace. Thanks in large part to Harry Bridges, the ILWU was the first union in the United States to actively fight against racism.

Throughout it's history the ILWU has held to the belief that only in a stable, secure, and peaceful world can social and economic justice be achieved for all. Accordingly, in the 1930s, the union blocked the shipment of supplies to the rising fascist nations in Europe and Asia, and supported the fledgling Republic of Spain in its uneven struggle against the Axis powers. In 1938, they refused to load scrap iron destined for Japan and presciently claimed the iron would return as bombs against the United States. During the war they predicted would come, the ILWU stood all but alone in their protests against the mass arrests of Japanese-Americans. And once the war was won, the union opposed the escalation of the arms race and the Cold War.

Vietnam

As early as 1954, Harry publicly condemned US policy in Indo-China and predicted with startling accuracy the perils of US involvement. In 1965, the ILWU called for an end to the war in Vietnam, the first American union to do so, and demanded that the United States implement the "free elections that were called for by the Geneva Accords of 1954."

South Africa

In 1960, Harry Bridges and the ILWU reacted to the Sharpsville Massacre in South Africa by a launching a 30 year battle against apartheid. They were the first union in the United States to do so. Once again they had weighed in on the side of racial equality and equal opportunity. Over the years, the longshoremen raised money, pressured governments around the world, and refused to handle cargo destined for South Africa. They honored picket lines raised by CORE, the NAACP, and all other anti-apartheid activists.

In 1973, the ILWU called for a termination of all U.S. trade with South Africa, an end to arms sales, the imposition of economic sanctions on firms doing business there, and the denial of U.S. airports and docks to South African carriers. They demanded that the U.S. ban import-export bank guarantees on private loans to South Africa, and deny tax credits to U.S. companies operating there.

In 1978, the union divested all ILWU pension funds of stocks and bonds in companies doing business in South Africa, and cast their proxies to encourage other institutions to do likewise.

Upon his release from twenty-seven years of imprisonment, the President of a new South Africa, Nelson Mandela, came to the Bay Area and publicly expressed his gratitude to Harry Bridges and the ILWU for their steadfast support.

International Solidarity

Through the 1970s and 1980s the ILWU took a firm stand against military dictatorships in Central and South America. They boycotted cargo destined for Chile and El Salvador and played a key role in the national protest against torture and other human rights violations. They have been deeply involved in the fight to protect and expand labor rights throughout the region through visiting worker delegations, a program that first began in 1948. The union has gone far to support fair trade and to support workers and their unions around the world in their struggle for basic trade union rights: freedom of association, free collective bargaining, and fair representation.

Health and housing

Closer to home, the ILWU pioneered group health insurance, including preventative medical care, vision, and dental insurance for workers and their families, with little or no co-payment., They created the first union dental plan covering children. In 1963 the ILWU became the first West Coast union to invest in affordable housing for low-income workers. St. Francis Square cooperative housing project and Amancio Ergina Village were built in San Francisco with union pension funds. Similar projects for low-income workers and senior citizens were built by Local 142 in Hawaii.

"Undesirable alien"

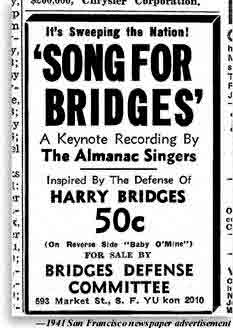

No such programs come without a cost. Harry and his union were marked early for destruction. Harry himself survived at least three assassination attempts, and was hounded for more than twenty years by J. Edgar Hoover and the Justice Department. In 1936 and 1939 he was classified as an "undesirable alien" and alleged to be a member of the Communist Party. Both times the charges were dismissed.

In 1940 a bill passed the House specifically marking him for deportation (it died in the Senate). But he was arrested that same year, and once more in 1945, on the same tired charges of being a secret member of the Communist Party.

The Supreme Court attempted to call the campaign to a halt: "The record in this case will stand forever as a monument to man's intolerance to man," wrote Justice Frank Murphy. "Seldom if ever in the history of this nation has there been such a concentrated, relentless crusade to deport an individual simply because he dared to exercise the freedoms guaranteed to him by the Constitution." But in 1951, Bridges was jailed again for criticizing the Korean War, and in 1955 he was tried in a civil suit calling again for his deportation.

During the McCarthy Era, the ILWU was expelled from the suddenly

right-leaning CIO for refusing to relinquish their rank-and-file's

democratic right to determine which presidential candidate would gain

their support. Ten other progressive unions were also expelled on this

pretext and most were eventually destroyed. But the ILWU survived - not

only with its membership and ideals intact, but, under the leadership of

Harry Bridges, the union became a refuge for blacklisted workers from

across the nation.

During the McCarthy Era, the ILWU was expelled from the suddenly

right-leaning CIO for refusing to relinquish their rank-and-file's

democratic right to determine which presidential candidate would gain

their support. Ten other progressive unions were also expelled on this

pretext and most were eventually destroyed. But the ILWU survived - not

only with its membership and ideals intact, but, under the leadership of

Harry Bridges, the union became a refuge for blacklisted workers from

across the nation.

"An ennobling example for generations to come."

Now, a decade after his death, historians are ranking Harry Bridges with the giants of labor: Eugene Debs, Big Bill Haywood, John L. Lewis, and even, oddly enough, the conservative Samuel Gompers. And it is clear that no other man's jousts with the federal government have done more to broaden and strengthen the Constitutional rights of immigrants, political dissenters, and racial minorities. The historian Charles Larrowe wrote of Harry Bridges:

His life remains what it is, with the flaws and frailties to which we are all vulnerable, an ennobling example for generations to come. For he is a man who fought back against forces which, time after time, seemed overwhelming: the awesome power of a government determined to crush him; the employers and their allies bent on breaking him; the official labor movement, which tried to silence him by putting him beyond the pale.

And through it all, Harry Bridges never wavered. He remained true to the interests of ordinary working citizens. He accomplished great things for San Francisco, for California, and for the nation at large. He fought all his life so that others could live with dignity and pride, and for that alone he deserves to be honored by any city, but especially San Francisco, the city that was his home.

Notes

Many thanks to Grif Fariello for permission to add this article to the Union Songs web site